Common culprits are cracked rubber hoses, a bad PCV valve or hose (PCV valve vacuum leak), a loose intake boot, or a leaking intake manifold gasket. You might also hear a hiss, have a hard brake pedal (brake booster vacuum leak), or see EVAP small leak codes from a loose gas cap. This perspective reflects Jerry’s has help to over 40,000 customers in accessing accurate repair prices and making sense of repairs.

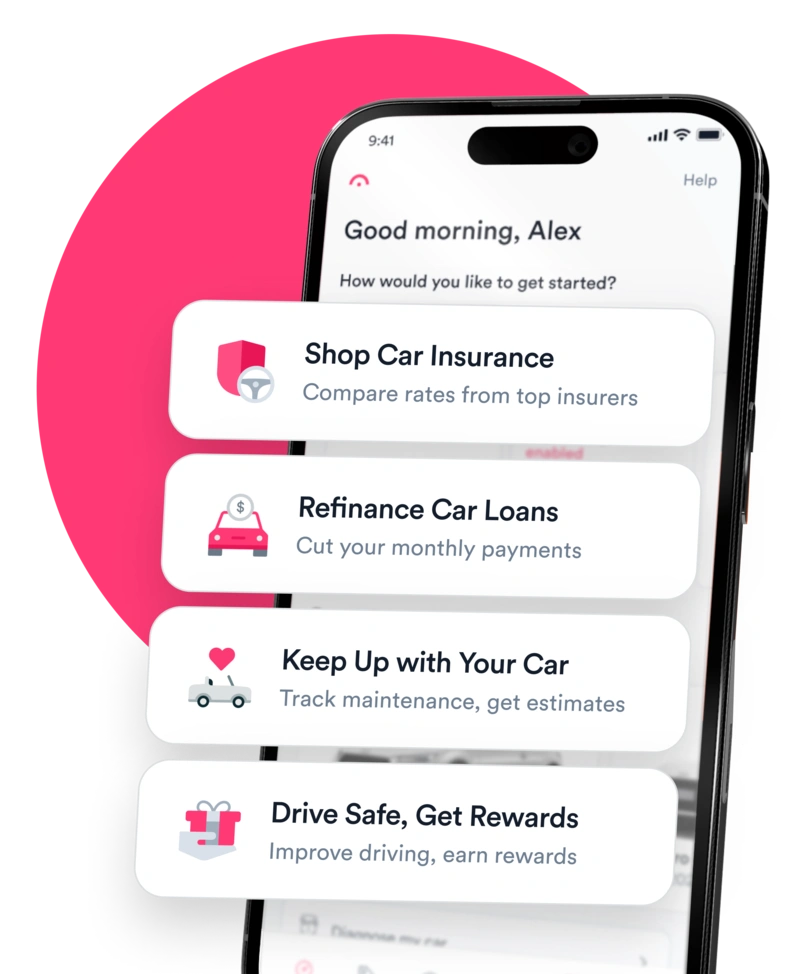

In this guide, you’ll learn how to find a vacuum leak, what’s safe, likely causes, typical fixes with prices, and when to call a pro. With the Jerry app, you can join other customers who’ve compared quotes and found the right shop for their repairs. You can also check open recalls, chat with AI about symptoms and set maintenance reminders. Download the Jerry app to get started.

Real customers Jerry helped

While pricing can vary based on different factors like location, parts used, and exact vehicle, Jerry uses real customer experiences to show what drivers are paying right now. Here are a few customer examples:

Estimates are modeled based on real vehicle and location data; names have been changed. Actual prices will vary by shop, parts, and vehicle condition.

At-a-glance: can I keep driving?

If you suspect a vacuum leak, use your senses and the list below to decide how urgent it is. Small leaks can wait a bit; brake or severe idle issues need fast attention. Jerry customers are using these buckets to categorize risks:

- 🚨 Urgent — turn it off and get help now.

- Hard brake pedal or longer stops (possible brake booster vacuum leak).

- Engine stalls at idle in traffic (safety risk).

- Strong fuel smell plus Check Engine Light (fuel/EVAP issue or misfire risk — check for leaks; tow if unsafe).

- 🕒 Soon — okay to drive, fix this week.

- Rough or high idle, engine surging.

- Check Engine Light.

- Noticeably worse fuel economy or hesitation.

- ✅ Monitor — safe to drive.

- Faint hiss from the engine bay with no drivability change.

- HVAC vents stuck on defrost in older cars but brakes/drive fine.

These buckets matter because vacuum affects critical systems, like brake assist and maintaining proper air/fuel ratio for optimal engine performance.

Symptoms

Here’s how common driver-facing symptoms map to likely causes and the usual fixes. Prices are typical U.S. ballparks for Jerry customers and can vary by engine layout and region.

Risks if you ignore it

Vacuum leaks start small but can snowball. Jerry customers are finding that acting early helps. Here’s why:

Longer stopping distances: a leaking brake booster reduces brake assist.

Engine damage risk: running lean can overheat valves and pistons over time.

Catalytic converter wear: misfires from bad fueling can overheat and ruin the cat.

Higher fuel bills: the ECU adds fuel to mask the leak, killing mpg.

Emissions and inspection test failures.

Most early fixes are hundreds, not thousands, if you address them quickly.

Can I repair this myself? (DIY vs. pro)

Vacuum issues range from simple hose fixes to gasket replacements. Start simple and safe, then escalate to a shop for testing and sealing. Remember to use Jerry’s insights into parts and labor rates to make a clear decision on your approach. Safety protocols: engine cool, park on level ground, wear eye protection.

- DIY (easy, low risk):

- Inspect rubber hoses and the intake boot: look for cracks, splits, and loose clamps; replace brittle hoses to stop unmetered air.

- Listen for hissing: Use a short piece of hose as a “stethoscope” to pinpoint noisy areas without touching hot parts.

- Read codes with a basic OBD-II reader: Note codes (don’t clear) so a tech can see freeze-frame data and fuel trims.

- Test brake pedal feel safely in a lot: If the pedal is hard, park it and tow — the brake booster needs a reliable vacuum source to operate properly.

- Turbo: Use light soapy water and very low pressure (<5 psi) on charge pipes to spot bubbles at leaks.

- Helpful tools: OBD-II app, hose pinch pliers, silicone vacuum hose, spring clamps, mirror/flashlight, mechanic’s stethoscope.

- Pro (recommended):

- Smoke test purge PCV/throttle as needed to isolate zones; harmless vapor finds hairline leaks fast.

- Data-driven diagnosis: check OBD-II fuel trims at idle and 2500 rpm, MAF/MAP plausibility, misfire counters; rule out upstream exhaust leaks that mimic lean.

- Repair and reseal: replace cracked hoses, PCV valve/lines, intake or throttle body gaskets; torque to spec.

- Brake booster and check valve testing: verify vacuum supply and replace faulty parts.

- Special notes:

- Turbo engines have more hoses and clamps; pressure and smoke testing are key.

- Hybrids may use electric vacuum pumps — extra diagnostics and higher parts cost.

- What NOT to do:

- Don’t drive with a hard brake pedal — get it towed for safety.

- Don’t spray flammable cleaners on a hot engine to “find leaks.”

- Don’t clear codes before diagnosis — you’ll erase useful clues.

Prevention

Jerry customers are following a few simple habits to keep rubber healthy and leaks at bay. Build these into your routine.

Inspect vacuum hoses and the intake boot every 12 months or 12,000 miles; replace any that are soft, oil-soaked, or cracked.

Replace the PCV valve and its hoses around 60,000 to 90,000 miles to prevent sludge and leaks.

Keep your air filter clean (15,000 to 30,000 miles) so the mass airflow sensor reads correctly and clamps stay clean and tight.

Fix oil leaks quickly — oil degrades rubber hoses and gaskets.

After any major engine work, recheck clamps and hoses after 500 miles; heat cycles can loosen them.

For older cars with vacuum heating and air conditioning controls, inspect the vacuum reservoir and one-way valves annually.

In cold climates, check hoses before winter; cold can crack aged rubber.

As an example of smog test troubles, I was once trying to get a 1964 Chevelle registered, and that was back when you had to add devices to pass a smog test. At the smog station, the technicians raised the hood, looked at the added devices and ran the car on the dynamometer. The car passed the dyno test, but flunked the “visual” test because some of the hoses weren’t correct. So, I took the car back, made sure everything was 100% and went back for another smog test. The car passed the dyno test again. But, as I’m waiting for the “visual” inspection, they simply drove it off the dyno and gave it back to me. They didn’t even raise the hood! I muttered at the inconsistencies in the world of smog.

What our customers are asking us

-

Is it safe to drive with a vacuum leak?

-

What’s “normal” engine hiss?

-

How much does diagnosis cost?

-

Could a loose gas cause the Check Engine Light to come on?

-

Why does cold weather make it worse?

-

How do shops find tiny leaks?

-

Do turbo cars behave differently with a vacuum leak?

-

Are there recalls or technical service bulletins (TSBs) for vacuum leaks?

Steve Kaleff began working on cars at the very young age of nine years old, when his dad actually let him make fixes on the family car. Fast forward to the beginning of a professional career working at independent repair shops and then transitioning to new car dealerships. His experience was with Mercedes-Benz, where Steve was a technician for ten years, four of those years solving problems that no one could or wanted to fix. He moved up to shop foreman and then service manager for 15 years. There have been tremendous changes in automotive technology since Steve started his professional career, so here’s looking forward to an electric future!

Nick Wilson is an editor, writer, and instructor across various subjects. His past experience includes writing and editorial projects in technical, popular, and academic settings, and he has taught humanities courses to countless students in the college classroom. In his free time, he pursues academic research, works on his own writing projects, and enjoys the ordered chaos of life with his wife and kids.